So now we know that he's back in, the new question is 'can he win?'

Much has changed in Maryland since 2002 when Ehrlich became the state’s first Republican governor since Spiro Agnew in 1966, defeating then Lieutenant Governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend by a margin of 51.6% to 47.7%. Some of that change was already taking shape in 2006 when Ehrlich lost his bid for re-election to O’Malley by 52.2% to 46.2%. No doubt Ehrlich and his most trusted advisers have been surveying the Maryland political landscape and though he may not be looking for advice or insight from the halls of academia, I offer it nonetheless. He is free to accept or ignore it. In my examination of his chances, Ehrlich can find cause for concern and for encouragement. Overall, I conclude that Ehrlich’s road back to Annapolis would be steep, but not insurmountable. The success of his journey would likely rely as much on national political trends as it would on issues specific to Maryland.

The Bad News

The first thing Ehrlich must contend with is the overwhelming partisan advantage enjoyed by Democrats in the Free State. As of October 2009 the State Board of Elections reports that 56.8% of registered voters are Democrats, while only 26.6% are Republicans. Approximately 14% are unaffiliated and the rest belong to a scattering of minor parties. That two-to-one party advantage should give any potential GOP candidate pause and the trend in partisan advantage should be cause for nightmares. Since Ehrlich’s victory in 2002, Maryland Democrats have added just over 384,000 new voters to their ranks. During that same time, the Republican ranks grew by only 73,000. Since 2006 Democrats have added 204,000 voters to the party rolls while Republican ranks shrank by 3,000. In 2002, Republicans accounted for 30% of all registered voters and the Democrats 56%. So in the 7 years since Maryland last elected a Republican Democrats have padded there partisan advantage by about 0.8% while Republicans have seen their party position eroded by 3.4%. These numbers should matter to Ehrlich given that he defeated Townsend by only 67,000 votes and lost to O’Malley by nearly 117,000. Any strategist would look to the margin of loss in 2006 and question how it could be overcome when the Democrats’ ranks have been growing at a rate five times that of the Republicans’.

The Good News

Well that’s the bad news for Ehrlich – the Democratic Party has been growing its advantage among registered voters as the GOP has seen its share decline. So what’s the good news? It can be seen in the seemingly daunting statistics that I have already shared. In 2002, Democrats enjoyed a 56% to 30% advantage among Maryland’s registered voters – yet Ehrlich won nearly 52% of the vote. By 2006, Republicans had fallen to 28.9% of registered voters and Ehrlich still managed 46%. Clearly the Democrats’ registration advantage and the GOP’s disadvantage do not directly correlate to final vote totals. In fact, a review of the last four gubernatorial elections in Maryland (1994, 1998, 2002, and 2006) shows that the Democratic candidate typically and significantly under-perform in final vote totals relative to their party registration advantage and the Republican candidate typically and significantly over-performs. It is in that level of over and under performance that Ehrlich can find a path back to Annapolis.

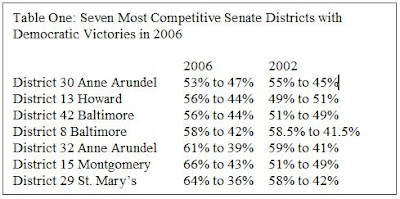

As shown in Table One, in all but one of the last four gubernatorial elections the Democratic candidate received a total statewide vote that was less than their party’s partisan registration advantage among those who voted. In 1994 879,842 Democrats cast ballots, but the Democratic candidate received only 708,094 total votes – the Democrat under-performed relative to partisan advantage receiving a total statewide vote equaling only 80.5% of the total Democrats voting. On the Republican side, GOP candidate always over-perform. Looking again to 1994 only 451,256 Republicans cast votes, but the Republican candidate received 702,101 votes. The Republican candidate over-performed by 155.6%. In all but one election, 1998, the Democratic candidate underperformed and in every election the Republican candidate over-performed. This means that in most of the recent gubernatorial elections many registered Democrats voted Republican as did many of the unaffiliated and third party voters. There is no other way to explain the under and over performance by the parties.

Table One tells us more than just levels of party performance. The grey boxes indicate the winning candidate in each election. As shown, the Democratic Candidate won in 1994, 1998, and 2006. The Republican candidate won in 2002 – the election in which Ehrlich defeated Townsend. So Democrats won 3 of the last 4 gubernatorial elections, but look closely at 1994- the margin of victory is very small. In 1994 Democratic candidate Parris Glenndening defeated Republican Candidate Ellen Sauerbrey by a scant 5,993 votes. In 1998 and 2006 the Democrat victory margins were more significant. The 1994 and 2002 results show that Republicans can win in Maryland so long as the GOP candidate significantly over performs and the Democratic candidate underperforms. In 1994 and 2002 the Democrat under-performed by 80.5% and 83% respectively and GOP candidate over-performed by 155.6% and 156.5%. Conversely, Democrats won decisively in 1998 and 2006 when their candidate performed on par with their partisan share of the electorate and the GOP candidate’s level of over-performance declined.

This is important because of the two election cycles when the Republicans performed best and the Democrats worst – 1994 and 2002. 1994 was the year of the Republican revolution that resulted in the GOP recapturing the House of Representatives and the Senate for the first time in more than a generation. 1994 was the first mid-term election after Bill Clinton’s 1993 election and the election was largely viewed as a referendum on his very uneven first 18 months in office. Likewise, 2002 was a very strong year for Republicans. Since Reconstruction, only three presidents have enjoyed mid-term electoral victories in Congress: FDR in 1934, Bill Clinton in 1998, and George W. Bush in 2002. So the 1994 and 2002 mid-terms were very good for Republicans nationally and the strong Republican showing in the Maryland gubernatorial elections were a reflection of that national trend.

In contrast, 1998 and 2006 were good years for Democrats. In 1998 a rebounding and re-elected Bill Clinton saw his party gain seats in the House of Representatives as an impeachment wary public expressed disapproval of Congressional Republicans. Much as in 2006 when a war weary nation stripped Republicans of there majorities in the House and Senate and delivered control to the Democrats. So 1998 and 2006 were good years for Democrats nationally and that translated into the strong showing by Democrats in the Maryland gubernatorial elections.

Implications for Ehrlich

So what does all of this mean for Ehrlich and 2010? It means that Ehrlich has to decide whether he thinks that the 2010 mid-term election will be like 1994 and 2002 – in which case he has a decent chance at reclaiming his old job – or will 2010 be closer to 1998 and 2006 – in which case he should let the Maryland GOP designate some other sacrificial lamb. Once that decision has been made, he must consider whether the Democratic Party’s current registration advantage, or rather the Republican Party’s disadvantage, can be overcome.

Will 2010 be a GOP Year?

If current indicators are to be trusted then the 2010 election is shaping up to be a mid-term in the 1994/2002 mold. Consider the evidence:

- According to most polls, registered voters would prefer a Republican over a Democratic candidate in November. Gallup reports that Republicans have rarely held an advantage on the generic ballot dating back to 1950. Two exceptions occurred in 1994 and 2002.

- Independent and moderate voters are expressing a clear preference for the Republican candidate.

- In 1994, the Republican wave that swept the Democrats out of power in the House and Senate was presaged by Republican gubernatorial victories in Virginia and New Jersey in 1993. Republicans scored clear victories in both states in 2009, largely a result strong support from Independents.

- The surprise victory by Republican Scott Brown in Massachusetts is also a bad omen for Democrats and offers some hints to how Ehrlich could win in Maryland.

- Add to this the latest edition of the Cook Political Report which has identified 50 competitive House seats heading into 2010. Of the 50, 39 (or 78%) are held by Democrats.

Even if 2010 mimics 1994 and 2002, Ehrlich must decide whether or not a strong GOP wave would be sufficient to overcome the tremendous registration advantage enjoyed by the Democrats. To try and answer I examined statewide registration and turnout data to estimate how a 1994 or 2002 election would translate with 2009 registration numbers.

Table Two shows Democratic and Republican Party turnout in each of the four elections discussed. Republican turn-out is consistently higher than Democratic, but Republican turnout was highest in the years that Republicans did well and Democratic Turn-out in 1994 and 2002 and was similar to the strong Democratic year in 1998. Democratic turnout was high the years when the party underperformed (Table One), suggesting that higher Democratic turnout may have represented registered Democrats voting Republican.

Using current voter registration data (October 2009) it is possible to model the potential outcome of an Ehrlich/O’Malley rematch based on prior turnout and over/underperformance levels for the Democratic and Republican parties. As of October 2009 there were 1,940,634 registered Democrats and 906,679 registered Republicans in Maryland, a 56.8% to 26.6% advantage.

As shown in Table Three, if the 2010 gubernatorial election follows the turnout and party performance patterns of 1994 or 2002 then Martin O’Malley would still be narrowly re-elected governor. These results reflect not only the increased registration advantaged enjoyed by the Democrats, but also the declining registration among Republicans. Even in a strong Republican year – like those in 1994 and 2002 – Ehrlich would face an uphill struggle against the Maryland Democratic Party’s registration advantage.

Could Ehrlich Win?

Despite the rather dire numbers presented in Table Three, Ehrlich would still have a fighting chance in a re-match with O’Malley. If Ehrlich could match the level of over-performance that he mustered in 2002 he would stand to receive 957,162 votes, and if Democratic underperformance were to fall to 1994 levels O’Malley would receive 952,336 votes. Ehrlich would win, though barely. In the end, Ehrlich’s best hopes lie within data than cannot be incorporated into the turnout models in Table Three. When Ehrlich and O’Malley faced off in 2006 Ehrlich was the Republican incumbent in a year that was bad for Republicans. In 2010, O’Malley will be running as a Democratic incumbent in a year that is likely to be bad for Democrats and incumbents. O’Malley will be running on his record and potentially against a strong anti-incumbent tide.

The latest poll in the Maryland governor's race shows incumbent Martin O'Malley with a 6 point lead over potential rival, and former governor, Bob Ehrlich - the race stands at 49% to 43%. The survey, by Rasmussen Reports, shows that O'Malley simply cannot crack 50% and polling below 50% is a bad sign for any incumbent. A Clarus poll taken late last year showed further danger for O’Malley as it found that only 39% of Maryland voters wanted to see O’Malley re-elected. When asked to rate O'Malley’s performance on 11 key state issues (taxes, budget, jobs) he only received majority approval on one issue – "living up to high standards of ethics."

There is no question but that Bob Ehrlich would face a steep climb back to Annapolis, he would likely need to ride a national wave similar those in 1994 and 2002. In addition, he would need to overcome the significant registration disadvantage among Republicans statewide, or work to reverse the trend over the next 7 months. He could also hope that many of the newly registered Democrats were motivated by the drama of the 2008 Democratic primary battle and subsequent presidential election and that the Democratic Party’s registration advantage is somewhat overstated. Democratic Party registration swelled in Virginia and New Jersey in 2008 as well, but this did not translate into any appreciable party advantage in the 2009 gubernatorial elections. Democratic Party registration in Maryland grew at a rate of about 2.5% between 1994 and 1998, then by 5% between 1998 and 2002, before swelling to 11% prior to the 2006 gubernatorial and 2008 presidential elections. That excess growth may overstate the Democrats’ true advantage in the state by as many as 200,000 voters. If one were to factor that into the models presented in Table Three then Ehrlich would win under either a 1994 or 2002 scenario by a margin similar to his 2002 victory over Townsend.

Even with the challenges he’ll face, 2010 will likely present his best chance at reclaiming his old job. If Ehrlich waited until 2014 he'd risk that it would be a less hospitable year than 2010. If a Republican is elected president in 2012 then history tells us that 2014 would be a bad year for Republicans. If Obama or another Democrat is elected in 2012, then 2014 may well be a good year for the GOP, but in Maryland Ehrlich would have been out of public office for 8 years and could no longer assume the position of presumptive frontrunner for the nomination. Ehrlich would face much the same challenge if he were to decide to pursue one of Maryland’s Senate seats. Democratic Senator Barbara Mikulski is up for re-election in 2010, but nothing less than a GOP tsunami would defeat her. Ehrlich’s next chance would be 2012 when the seat held by Democratic Senator Ben Cardin would be on the ballot – but president Obama would be on the ballot as well in a state that he carried by a margin of 62% to 37%. Anything approaching that margin would likely have some down-ballot coattails and sink any challenge to Cardin or another Democrat.

In the end, for all the challenges and difficulties that he'll face, 2010 presents Ehrlich with his best chance for reclaiming the governorship. For Ehrlich, it's now or never. And he has decided that it's now.

More on the Ehrlich/O'Malley race can be found here and the impact of Enrlich's run on Republican efforts to gain 5 seats and reach 19 (the number needed sustain a filibuster) in the Maryland Assembly can be found here.

More on the Ehrlich/O'Malley race can be found here and the impact of Enrlich's run on Republican efforts to gain 5 seats and reach 19 (the number needed sustain a filibuster) in the Maryland Assembly can be found here.